Though this is not my first blog, this is the first blog in which I plan to focus solely on discussing my experiences of living with Cerebral Palsy and the process of getting these experiences eventually published. Specifically, my goal is to raise awareness for Cerebral Palsy and other disabilities and allow others to gain a deeper understanding of what it’s like to live with a physical disability.

To kick off this blog and a new chapter of sharing my story of living with CP with others, here is rough draft of the talk I have been giving to elementary and middle schools in Buncombe County since November 2013:

I was born with Cerebral Palsy, a disability that affects my nerves and my muscles, causing me to walk differently than most people. I’ve had multiple intense surgeries and 15 years of physical therapy. My Cerebral Palsy affects the way I walk because my muscles are really tight and because I don’t have very good balance. Because of being physically different, I was always an outcast in school. I had trouble making friends, and it was hard not having someone who knew what I struggled with on a daily basis. When I walk, it is very evident that I am different, and because of my visible differences, I was an easy target for bullying in school.

I had my first bullying experience when I was in kindergarten. At that age, I had to use canes to help me walk. Because of having to use canes, I wasn’t able to walk very quickly, and there was a girl named Ashley who enjoyed picking on me because she knew I wouldn’t be able to run away from her. Every day on the playground during recess, Ashley came up behind me and pulled my hair. It wasn’t a friendly pull either. She grabbed a fistful of my hair and yanked as hard as she could, laughing as I screamed in pain. She pulled so hard that I couldn’t even try to get away from her. Every day, I came home crying, and every morning, I woke up dreading having to go to school and see Ashley on the playground. I felt like crying when I realized I was completely alone and there was no one willing to stick up for me. One day, my teacher, Miss Sandy, came up to me and told me to hit Ashley with one of my canes to help her realize that what she was doing was hurting me. See, Ashley was mentally disabled, so she didn’t know any better, and hitting her was one of the only ways Miss Sandy knew to make her stop. I never did hit Ashley though. I couldn’t do it. Hitting her would make me just like her: someone who wanted to hurt someone else. I don’t think Miss Sandy really wanted me to hit Ashley though. She was just trying to teach me the importance of standing up for myself. In many ways, it felt impossible. How was I supposed to stand up for myself when it felt like I didn’t have a friend who would stand up for me?

I’ve struggled with forming friendships my entire life. As a kid, I wanted friends more than anything. That’s why I never told a teacher that kids were making fun of me. I became afraid that once I told a teacher, the people who picked on me would call me a “tattle-tale” and the other kids would distance themselves even more. Because I was so physically different from the other kids in my class, all I wanted was to feel like I fit in. In my early friendships, many of the people who became friends with me were my friends out of pity. Even though they didn’t specifically tell me so, I could tell it was true. I could tell by the way they looked at me that they felt sorry for me. When I was young, I kept those friendships anyway because all I wanted was a place where I felt like I belonged. However, many of those friendships didn’t last long because most of the people who had been spending time with me left when they got tired of pretending to be my friend.

It wasn’t until I became friends with a boy named Tommy in first grade that things began to change. Tommy was the first person to visibly stick up for me. He confronted the people who picked on me, telling them it wasn’t okay to pick on someone who couldn’t help that she was different. Tommy’s friends laughed at him for sticking up for me, but he didn’t care. He stuck up for me anyway and was there for me no matter what. Tommy also saw the numerous people who became friends with me because they felt sorry for me. He knew how much that hurt me. Even though Tommy wasn’t disabled, he saw how I cried day after day when another person I thought was my friend just got tired of trying. Tommy’s presence in my life didn’t stop other kids from picking on me, but I began to feel a little less alone. Even now, I don’t have many friends. However, the few friends I do have are incredibly close to me, and I am happy to say that one of those friends is still Tommy.

When I was in fifth grade, I took a required PE class. In my PE class, dodge ball was typically the game of choice. Every week in PE, I was chosen last for dodge ball. I even remember one particular day when one of my friends, Allison, was the team caption. This made me excited because I thought: Yes, finally! I won’t be picked last! Allison will choose me since we’re friends. Each team captain began to choose players, and I waited with excitement for Allison to say my name. I looked towards her with a smile on my face, but my smile faded as I realized she was picking everyone else but me. Finally, it came down to Miranda, a girl who had just broken her leg, and me. It was Allison’s turn to pick, and I started to inch towards her. And then you know what happened? She chose Miranda over me! Miranda, the girl no one liked because she was so mean, and the girl who couldn’t even move as well as me because she had broken her leg. I couldn’t believe it!

I was incredibly sad from being picked last for dodge ball, but you know what? That wasn’t even the worst part. The worst part was seeing a girl named Rachel holding a dodge ball in her hands, a small smile on her face when she saw me, already eager to pelt me in the face with the ball. When the dodge ball game started, I hung towards the back. Despite dreading having to play this game every week, I knew a few tricks. I knew staying along the back wall was the best way to not get out immediately, and I knew I’d be one of the last players remaining on my team primarily for this reason. Therefore, the goal was to simply wait for the rest of my teammates to get out. You would assume the waiting part was easy, but it wasn’t. It was just more time I spent wondering how hard I’d get pelted with a dodge ball. Once none of my other teammates remained and I was the only player left, I allowed myself to look over at the other team. By that point, the other team consisted of six players, and they each held a dodge ball. Six against one, and I didn’t even have my own dodge ball for defense. The players on the other team looked back and forth at each other, trying to decide who would have the pleasure of getting me out. Honestly though, I don’t know why they took time trying to decide. They all knew Rachel had to be the one to do it. Eventually, I looked over at Rachel, staring at her just as hard as she was staring at me. Right before she threw the ball, I saw her chuckle quietly to herself. A few moments later, the dodge ball hit me right in the face. The ball hit me so hard that I lost my balance, falling onto the hard surface of my school’s basketball court. Initially, I could hardly breathe, much less get up off the floor. My PE coach came over immediately to help me up and to scold Rachel for what she had done. However, I doubt Rachel ever got the scolding she deserved because I continued to get pelted with Rachel’s dodge balls throughout my entire fifth grade year.

As I got older, I thought the bullying would stop, but it didn’t. The summer after my sophomore year in high school, I attended a creative arts camp. One day I was walking back from a creative writing class, and out of the corner of my eye, I saw a girl named Lauren imitating the way I was walking. I turned to her and said, “Hey, what are you doing?” “Imitating the way you’re walking,” Lauren said. When I asked her why, she explained that she was supposed to observe and imitate people as an assignment for her theatre class. Even though I told her she hurt my feelings, Lauren didn’t listen. As I walked away, I watched as she laughed and continued to imitate me. I ran back to my room and cried, so sad and frustrated that I was still getting picked on. Even at an older age, getting picked on hurt just as much, if not more. Lauren knew what she had been doing. She saw how I cried in front of her, and yet she still continued to imitate me and laugh at me. I couldn’t understand why she would be so mean on purpose. I ended up telling a staff member about what happened, and she contacted the teacher to find out that the imitation was never a class assignment. The next day, though, something good happened. Lauren did the one thing I never thought she would ever do: she said she was sorry.

Being bullied, either physically or emotionally, is hurtful for anyone, but it’s especially hurtful if someone bullies you for something you have no control over, like a physical disability. My bullying experiences have affected me my entire life. I still remember the details of every bullying experience I’ve ever had. I still remember how alone and broken the experiences made me feel, and how it seemed like the bullying would never stop. Typically, kids in school try to be different because they don’t want to blend in with the crowd. For those kids, it’s important to stand out. In my case, I have always been incredibly different, and all I have ever wanted was to be normal and blend in. However, differences have never stopped me from trying to be as independent as possible. I have Cerebral Palsy, but I am a survivor.

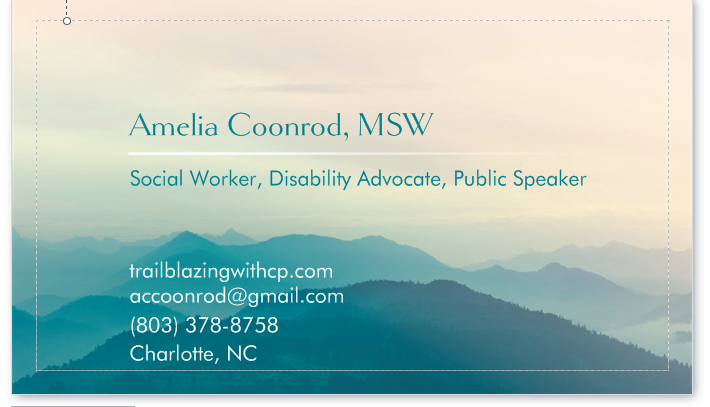

**If you are interested in having me come speak at your school, please have the school counselor at your school contact me via email at: accoonrod[at]gmail[dot]com**

Recent Comments